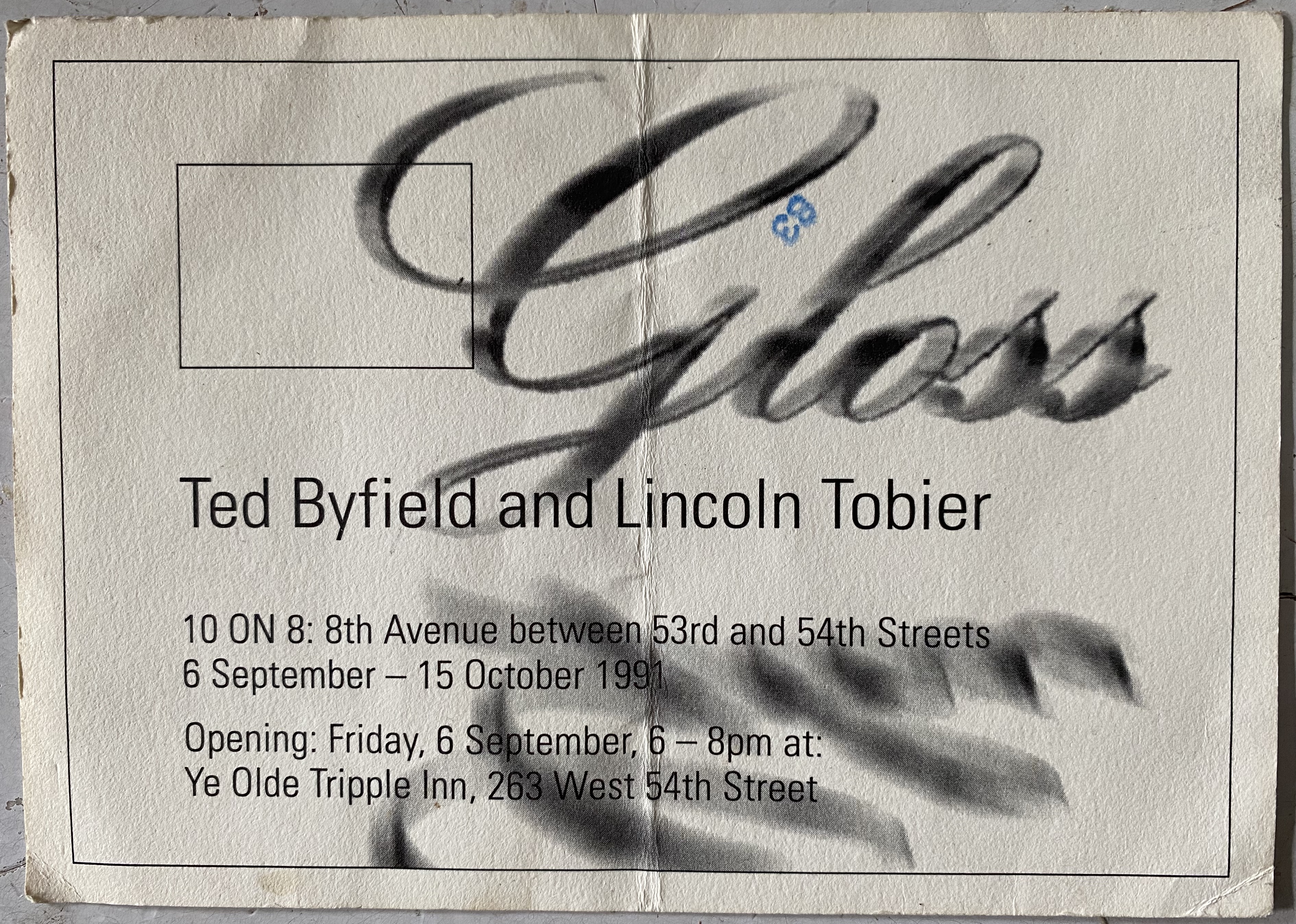

“Gloss” was the first exhibition I made with my then-collaborator, Lincoln Tobier at 10 on 8, a series of window enclosures built at eye level into the side of a garage on the east side of 8th Avenue between 52rd and 54th Streets. At the time, in 1991, a lot of aesthetic theory orbited around a new awareness that optical experience was not just culturally specific but historically contingent — a posh way of saying that how and what we see changes between from one culture and eras to the next. However, that Foucauldian line of thought was spawning lots totalizing assumptions. For example, if various cultures and eras see differently, it was widely assumed, that implied that in a single place and time there was some overarching, normative (or, if you like, normy ) model. The style at the time among those who saw themselves as critical — one that lives on even now, unfortunately — was to pluck some ominous-sounding word from the ether and use it (or at least its tragic dimension) as if were more or less self-evident. So, for example, people began throwing around phrases like Martin Jay’s scopic regime. “Gloss” consisted of ten different ways of staging photographs that dealt with some aspect of visuality, often (bit not always) involving a transparent surface that coincided with some social barrier: from “visual cliff” experiments, to rioting police with plexiglas shields, to Peter Lorre seeing his reflection in a shop window in Fritz Lang’s film M, to Eichmann on trial in a bulletproof box. Each staging distorted the image spatially in some way — breaking it into layers. bending it, projecting it onto dimensional surfaces, juxtaposing it — to reveal non-obvious aspects of the images and question monolithic ideas of seeing. The essay “Television” grew out of this exhibition.